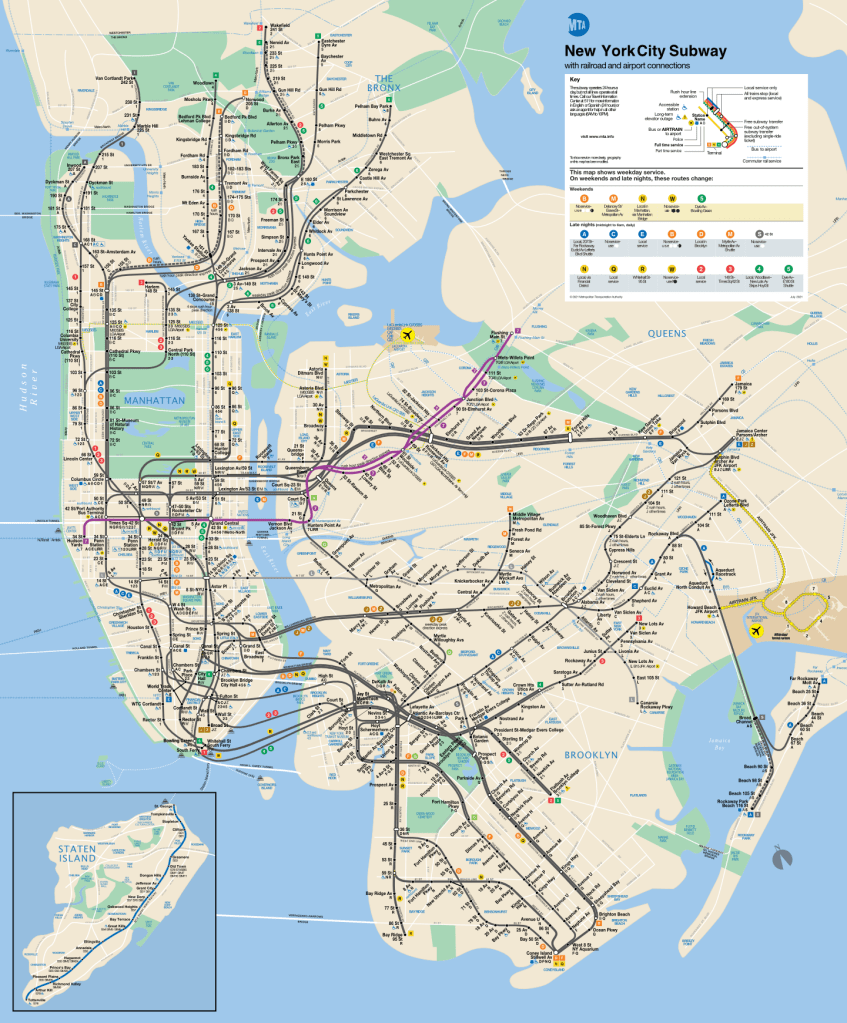

Manhattan

34th St-Hudson Yards (7)

34th St-Hudson Yards was initially planned as part of the city’s bid for the 2012 Olympics, and the often-proposed but never-built West Side Stadium. The station opened in 2015, three years too late for the Olympics, which didn’t happen in New York anyway, and was the first new station the city had seen since 1989. The station platform is one of the widest in the system, clocking in at 11m (~35 light-nanoseconds) and the platforms are some of the longest in the IRT system. It is also the longest column-free platform in the system. The record breaking platform is part of the station’s designed capacity of 40,000 passengers a day, expected on days when events are being held at the nearby Javits Convention Center, however, the station has consistently fallen below these lofty expectations for ridership. The tail tracks extend south of the station all the way to 25th Street, and can each hold three trains.

The station is very deep, at 125 feet below street level, and 108 feet below sea level putting it at third deepest below street level and second deepest below sea level. For reference, the North River Tunnels, which carry Amtrak and New Jersey Transit under the Hudson River, are above the platform level. (The North River was the anglicized Dutch name of the Hudson River. The Dutch New Netherland Colony extended from the Delmarva Peninsula to Rhode Island, and the two main rivers of the colony were the Delaware, called the South River, and the Hudson, called the North River). The depth and platform offset from the entrances means that an incline elevator is possible, to carry passengers from the Hudson Boulevard entrances (in between 10th and 11th Avenues) to the mezzanine level, directly under 11th Avenue. The inclusion of an incline elevator was cheaper than a typical vertical elevator, but is incredibly slow. This was intentional, in order to prevent non-disabled passengers using it, however it seems like disabled passengers still get the short end of the stick with incredibly slow access to the station. The station, in particular the entrances, was inspired by Canary Wharf station in London, part of the Jubilee Line Extension that was built in the 1990s.

There was a planned station at 10th Ave, but this was not built due to a lack of funds, and a station shell was not put in place as a placeholder should the station be built in the future. The MTA currently cites $1 billion as the price tag for retroactively building the 10th Ave station.

Times Sq-42nd St (7)

From 1927 to 2015, Times Sq served as the western terminus for the IRT Flushing Line. While the station is named for 42nd Street, the IRT Flushing Line is actually located under 41st St.

Before 1949, the line between here and Queensboro Plaza, a two-track subway, was known as the Queensboro Line, whereas the line east of Queensboro Plaza, a three-track el, was known as either the Corona (yikes, I know) or Flushing Line. This is because until 1949, trains from “the Queensboro Line” (Times Square to Queensboro Plaza) could serve both (what is now) the BMT Astoria Line and the IRT Flushing Line. Today, (7) trains exclusively serve the 42nd St “Queensboro Line” and the “Corona El”, creating one continuous IRT Flushing Line. We will get back to this a little bit later.

Grand Central-42nd St (7)

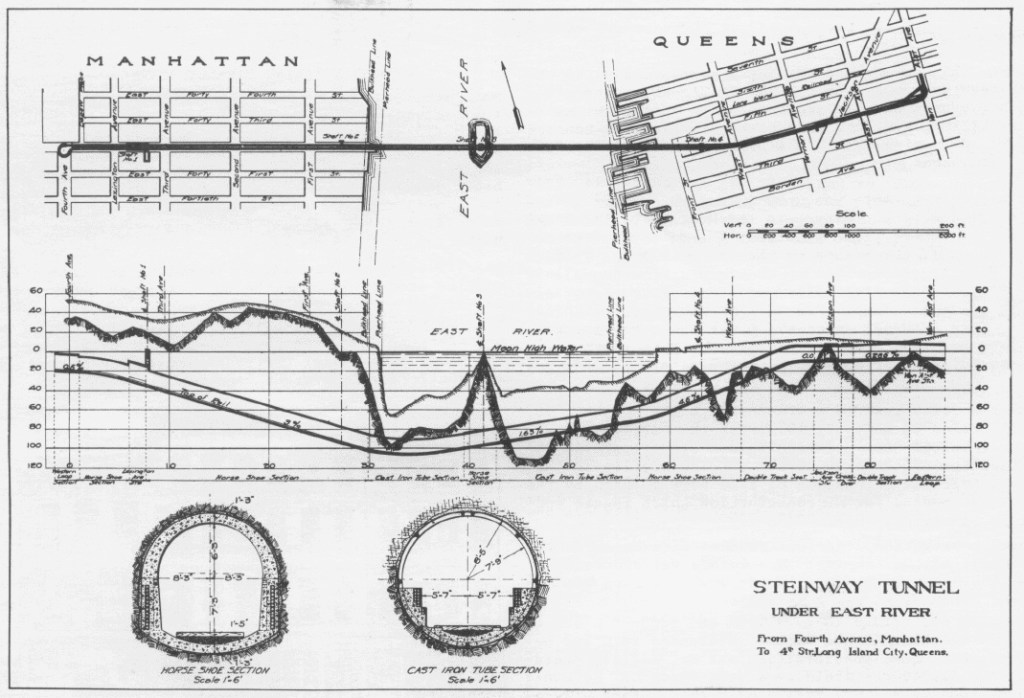

The IRT Flushing Line platform level of the Grand Central station is situated in one large cavern deep underground, similar to some deep level stations in London or former Soviet systems. Grand Central is the western end of the Steinway Tunnel, the name for the tunnel that the IRT Flushing Line travels through to reach Queens. The history of this tunnel is rather fascinating, if the history of subway tunnels is the kind of thing that fascinates you.

The initial plan for the tunnel came about in 1885, with the intention of connecting the Long Island Railroad (LIRR) with the New York Central (NYC, now Metro-North). The LIRR had a terminal in Long Island City, which still stands today, and the NYC had just built a station called Grand Central Depot at Park Avenue and 42nd Street. The many waterways of New York City made reaching downtown Manhattan difficult (Midtown was not yet a destination in and of itself) without a river crossing, so most railroad companies employed the use of ferries and streetcars to bring passengers from Brooklyn, Queens, and New Jersey into the central business district of Manhattan. This arrangement was frustrating for commuters, and also meant that New York City area railroads couldn’t interchange passengers or freight with each other very easily.

The East River Tunnel Railroad Company, which had been formed to build this tunnel, was dissolved after running out of money, and in 1887 a new company, the New York & Long Island Railroad, was formed to take the project over. The new plan was for a tunnel to connect the docks on the Hudson River with the LIRR in Long Island City via a tunnel under 42nd St. Ironically, this is very nearly what the IRT Flushing Line today does, although the existing route was in no part built by the New York & Long Island Railroad. William Steinway, of piano fame began funding the company, as he believed it would raise property prices in and around Long Island City and Astoria, where he had significant holdings. (He was absolutely right about this, although he died in 1896, well before the tunnel was complete). Long story short, this is why a street in Queens, a subway tunnel under the East River, and a piano company share the same name. Construction on the tunnel began in 1892, but a series of accidents and a stock market crash the following year saw construction stop and the tunnel boarded up.

August Belmont Jr. had formed the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) in 1899 and was awarded the franchise to operate the first subway in 1900, although it wouldn’t start service until 1904. The IRT then purchased the New York & Queens County Railway, which operated streetcar lines in Queens, as well as the New York & Long Island Railroad, which still owned the incomplete Steinway Tunnel. The IRT’s plan was to run streetcars from Queens through the tunnel to a loop station at Grand Central. A ramp would be built in Queens to connect the tunnel to the streetcar network. This was actually a fairly common practice, with streetcars from Brooklyn and Queens running over the Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Queensboro bridges into Manhattan, stopping at a large trolley terminal immediately after the bridge, and returning to their home borough. Streetcars from Manhattan would do the same, turning around in Brooklyn or Queens. This would be the same, however through a tunnel, rather than over a bridge. The Queensboro Bridge would actually not open until 1909, so the streetcar tunnel would have been the first connection between Queens and Manhattan.

Belmont’s concession to legally run streetcars through the tunnel had expired on January 1, 1907, before the tunnel was complete. A few streetcars ran through the tunnels in September of 1907 on demonstration runs, but true streetcar service wasn’t inaugurated. The Steinway tunnel was actually the first passenger rail tunnel under a river in New York City. The Joralemon Street tunnel, which carried the original IRT Subway from Bowling Green to Borough Hall wouldn’t open until 1908. The city legally prevented Belmont from running streetcars through the tunnels by not renewing his concession, and also didn’t let anyone operate a privately owned subway tunnel. (Even though the IRT and BMT were private companies operating subway lines, the physical tunnels themselves were owned by the city and operating franchises were granted to the private companies).

In 1913, the city signed the Dual Contracts with the IRT and BMT, and in that agreement, Belmont sold the tunnels to the city. They had sat empty and unused for six years. It was found that they had a suitable loading gauge (the constraining factors on train size, such as tunnel width and height, curve radius, platform dimensions, etc.) for IRT subway cars. The subway cars could not use the loops at Grand Central or in Queens, as they were too tight, but the tunnel itself was acceptable with only minor modifications. The IRT Flushing Line was planned as a part of the Dual Contracts, and work began to modify the Grand Central station for subway use. The streetcar loop still exists, although it is disconnected from the subway tracks. The space is now used as maintenance rooms, and apparently partially visible from the eastbound track, although I have been unsuccessful in seeing any evidence myself. The loop on the Queens side was destroyed during construction of the eastern extension. Shuttle service through the tunnel began between Vernon Ave and Grand Central in 1915. The line reached Queensboro Plaza in 1916, and Times Sq in 1927. The tunnels were steeper than most grades on the IRT, so special “Steinway-type” cars had to be ordered to operate the line with more powerful gear boxes, until 1949 when new subway cars were ordered that removed the need for the special gear box.

The track geometry of the station is exaggerated in this photo, and two things stand out. The first is that at the eastern end of the platform, where this photo was taken, the track and platform dip down. This is due to the steep gradient of the tunnel required to pass under the East River. The second is that as Queens-bound trains enter the station, the track is not entirely straight. The platform on the Hudson Yards-bound side is completely straight, by comparison. I believe, although with almost no evidence, that this is a remnant of the original Grand Central loop station for the streetcars.

The construction of the tunnel used an outcrop of granite in the middle of the East River named Man-O-War reef as a launch point of a construction shaft. The reef was expanded with the debris excavated by the construction of the tunnels, and became an island, named after August Belmont, Jr., the financier of the IRT. It has since been named U Thant Island, after the former Secretary General of the United Nations, the headquarters of which overlook the East River at 42nd St. The island is now a bird sanctuary and has restricted access.

Queens

Vernon Blvd-Jackson Ave (7)

Not much going on here, although the mosaic station name reads “Vernon-Jackson Ave’s” which makes it look like a possessive, like the station belongs to someone named Vernon-Jackson Ave. Also, Vernon is now a Boulevard, not an Avenue, so the tiles are out of date and no longer correct anyway.

Queensboro Plaza (7)(N)(W)

The Queensboro Plaza station is, in my opinion, one of, if not the, most interesting stations in the system. Aesthetically? Top of the line. Historically? A+. And if subway history and aesthetics are not what this blog is about, then I don’t know what it is about. Queensboro Plaza is shared with the BMT Astoria Line, so make sure to read that post as well.

In 1913, the city signed the Dual Contracts. These were two contracts (the clue is in the name), each signed with a private subway operator, in which the City would build miles and miles of new subway throughout New York, and each of the two private companies, the IRT and the BMT (Brooklyn Manhattan Transit) would operate services on these new lines. Two of these lines were in Queens, the Astoria Line and the Flushing Line. They would extend from a shared station, Queensboro Plaza, deep into Queens, which at that time was largely agricultural and rural. The express purpose of the Dual Contracts was to open up the city for development to decongest Manhattan, and the wide open fields of Queens were perfect for new housing.

Both the IRT and BMT were offered to share the franchises to operate the Queens Lines, however there was one snag. The Steinway Tunnel, which had originally been built for streetcars, was very narrow, and while IRT trains could fit, BMT trains, which were slightly wider, could not. This meant that shared platforms along the Astoria and Flushing Lines would either be too narrow for BMT trains to fit, or too wide for the IRT trains. The solution was to build the lines to IRT specifications, and use BMT Elevated trains, which could fit, to operate the BMT franchises. The plan was for BMT subway trains from Manhattan to terminate at Queensboro Plaza, where a cross platform transfer was available to BMT El trains to take passengers into Queens, thus avoiding the double fare of taking both the BMT and IRT. IRT trains, on the other hand, could travel through the station from Manhattan into Queens without a required transfer. All revenue generated on the two lines was to be shared between the companies.

In 1909 the Queensboro Bridge had been completed, with space for two tracks, which connected to the 2nd Ave Elevated Line (owned and operated by the IRT). The Steinway Tunnel, as we know, had been completed in 1907, and was purchased by the city for subway use in 1913. The Queensboro Plaza station, when it was fully operational, was twice the size it is today. Eight tracks across two levels, with four island platforms, compared to four tracks and two island platforms across two levels today. The southern half of the station was served by the IRT, with the IRT Queensboro Line from the Steinway Tunnel and the IRT 2nd Ave Line from the Queensboro Bridge across a platform from each other. Queens-bound trains were on the upper level, and Manhattan-bound trains were on the lower level.

In 1920, the 60th St Tunnel, carrying the BMT Broadway Line from Manhattan opened. This allowed the northern half of the station to be completed, with the southernmost tracks connected to the 60th St Tunnel and the northernmost tracks being used by the BMT El trains, across the platform. The BMT El trains ran in a strange pattern. For example, a train leaving Astoria heading south would enter the lower level of Queensboro Plaza, and then reverse and head to Flushing. Returning from Flushing, it would enter the upper level, then reverse and head to Astoria, where the pattern would start over. The BMT trains from the 60th St Tunnel would enter the upper level, continue to a tail track, reverse and enter the lower level for the return journey to Manhattan.

In 1949 the northern half of the station was entirely demolished, the platforms on the Astoria Line were shaved back to fit the wider BMT cars, and a connection was made between the tracks from the 60th St Tunnel and the former IRT 2nd Ave El tracks, which had ceased service in 1942. This action split the Queens lines into the BMT Astoria and the IRT Flushing Line, with the only cross platform transfer between the A Division (numbered trains) and the B Division (lettered trains). Also at this station is one of the only track connections between the two divisions, and the only connection not a part of yard.

33rd-46th Sts (7)

The next three stations, 33rd-Rawson St, 40th-Lowery St, and 46th-Bliss St are all located on a concrete viaduct above Queens Blvd. This is in contrast to the typical steel structure used for elevated lines in the rest of the city, and even on the rest of the IRT Flushing Line. Most stations on the IRT Flushing Line have double-barreled names, but here, one name is the current numbered street name, and the other is the former name of the street. The names of the streets were changed in the 1920s to the numbers, although the subway kept the names on the stations until 1998, when they were removed. In 2004, a local petition to reinstate the historical street names succeeded and the MTA re-added them back to the station signage.

The IRT Flushing Line, at the time of its construction, was built through some very rural areas. Queens, unlike Brooklyn or Manhattan, was largely agricultural even in the 1920s, with a few villages scattered throughout the county. The IRT Flushing Line, like all Dual Contracts lines, was built to help move the population off of Manhattan Island and into un- or underdeveloped land in the outer boroughs. The population of Manhattan peaked in the 1910s at around 2.5 million people. For context, today Manhattan has a population of 1.7 million people. Opponents of the line believed that it would never make the investment worth it, as a subway line was seen as useless serving agricultural fields. However, as expected, rapid development quickly followed the line’s construction, and by June of 1917, just two months after the line was opened between Queensboro Plaza and Alburtis Ave (now 103rd St), the line was carrying more than 350,000 people a month, already exceeding expectations.

74th St-Broadway/Jackson Heights-Roosevelt Ave (7)(E)(F)(M)(R)

Not much to say about the IRT Flushing Line platforms here. This station is an interchange with the IND Queens Blvd Line, and is a local station on the IRT Flushing Line, despite the high ridership. The Queens Blvd Line came through after the Flushing Line, and when the Flushing Line was built the planners prioritized the express station to line up with the interchange with the Long Island Railroad at 61st St-Woodside, two stops west of here. Once the Queens Blvd Line came through, it was impractical to convert to an express station.

I want to point out that both the IRT station and the IND station have double-barreled names, like most major stations in the city do (for example, Times Sq.-42nd St), and like most stations on the IRT Flushing Line (for example, 33rd-Rawson St or 61st St-Woodside). However, both stations use different names for their station, leading this one station to have four names. The IRT station is 74th St-Broadway, whereas the IND station is Jackson Heights-Roosevelt Ave. Confusingly, the IRT Flushing Line also has a station called Jackson Heights, one stop east at 82nd St.

111th St (7)

111th St is the first station east of the initial stage of the IRT Flushing Line. It opened in 1925, with the following two stations, Willets Point and Flushing-Main St opening in 1927 and 1928 respectively. 111th St is quite unusual, as it has five tracks, with four on the main level and one above. On the main level, the two outer tracks are the two local tracks and the two tracks in the middle terminate just west of the station, and are used for storing trains. East of the station, they pass underneath the eastbound local track and lead to the Corona Yard, where IRT Flushing Line trains are stored and maintained. The fifth track on the upper level is the “third track” used by peak direction express trains to and from Manhattan.

Mets-Willets Point (7)

This station was originally opened as a local station named Willets Point Blvd, and was actually situated slightly to the east of where the current station is. In 1936, just nine years after opening, it had to be massively expanded for the 1939 World’s Fair. According to the New York Times, on January 16th, 1937, the IRT Flushing Line was only double tracked, and had to be triple tracked in order to provide express service to the fairgrounds. However, the picture seen above showing the Queens Blvd concrete viaduct, taken in 1920, clearly shows (well as clearly as a photo taken in 1920 can show) three tracks. Perhaps the New York Times simply meant the extension east of Alburtis Ave, as it was still under construction to Flushing. However in 1913, when the New York City Board of Estimate voted to approve the extension to Flushing, it had already been planned as a three-track line. Maybe the New York Times really is fake news.

Regardless, the Willets Point station was rebuilt, slightly to the west of where the original station had been. The westbound local platform is significantly longer than the rest of the station, as the eastern end is the remnants of the original platform. The new station was an express stop, with two side platforms and a wide island platform. Willets Point has remained a heavily used station, with the 1964 Worlds Fair, Shea Stadium (now Citi Field) and the USTA National Tennis Center both located nearby.

Flushing-Main St (7)

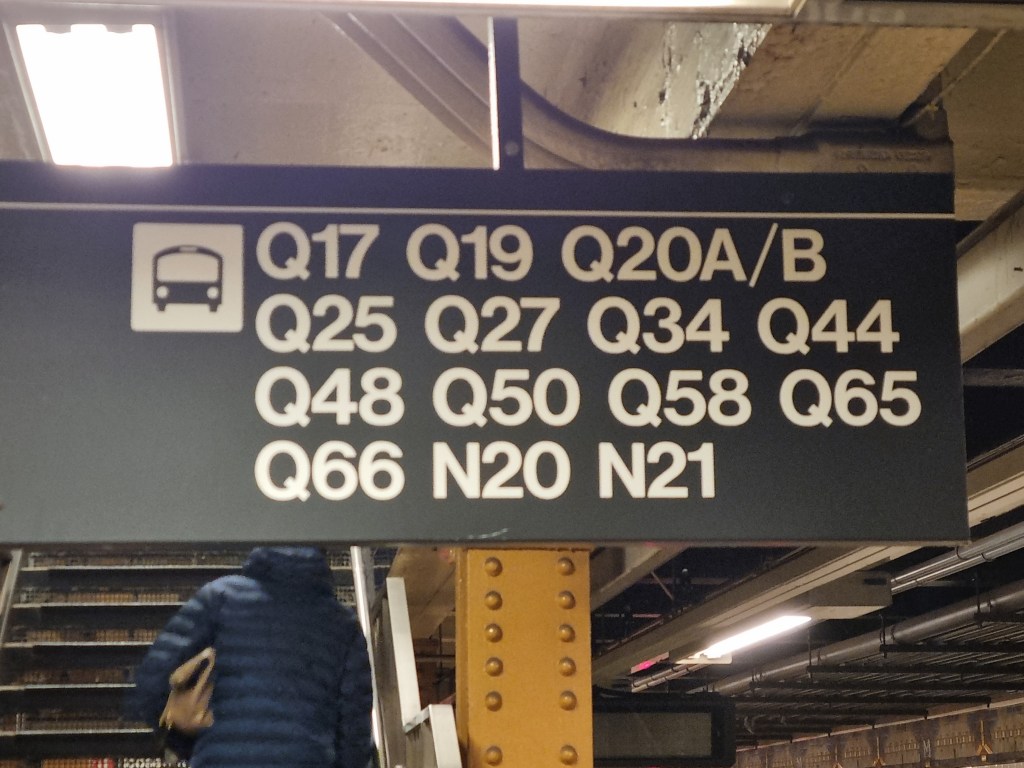

The Main St station is a three-track underground station. It is actually a terribly designed terminal, as it has no space for train storage, so all the switching has to occur in the way of other trains. It’s so poorly designed because it was never meant to be a terminal station. It is also one of the busiest terminal stations in the city. Many passengers continue onto buses, and so the (7) train is pretty much always crowded.

Unlike the area surrounding the rest of the line, Flushing was a real village before the subway came through. Flushing was founded by the Dutch West India Company as part of the New Netherland Colony in 1645, and named Vlissingen, after the Dutch town of the same name, where the Dutch West India Company was headquartered. Many of the residents in the town were British, as the Connecticut Colony was just across the Long Island Sound. The residents had all started calling the settlement “Vlishing” by 1657, and “Flushing” followed shortly after.

Flushing claims to be the birthplace of religious freedom in the New World. The 1645 Governor of New Netherland, William Kieft, granted the village of Flushing the same religious freedom as existed in the Netherlands, which was at the time the most religiously tolerant European nation. In 1656, Governor Peter Stuyvesant issued an edict banning all religious practice that was not conducted through the Dutch Reformed Church, targeted specifically at Quakers. In 1657, some 30 residents of Flushing, none of whom were Quakers themselves, signed the Flushing Remonstrance in response to the edict. A man named John Bowne held meetings for Quakers in his house in defiance of the law, and was deported to the Netherlands in 1662 for his crime, despite being an Englishman and not speaking Dutch. He managed to convince the Dutch West India Company to allow religious freedom in the colony, and in 1663, the Dutch West India Company sent a letter to Stuyvesant ordering him to end religious persecution in the colony. This has nothing to do with trains of course, but I learned about it when researching the IRT Flushing Line, and now you have as well. All of this to say, Flushing was very much an established settlement when the subway was being built, and the residents knew how to get what they wanted.

Since the beginning of the IRT Flushing Line’s planning, planned eastern extensions past Flushing have always been around. In fact, the Flushing-Main St station is only about halfway between the East River and the border between Queens and Nassau County. The towns of College Point, Whitestone, and Bayside all lie further into Queens than Flushing. At the time, eastern Queens was served by the Long Island Railroad, specifically the Port Washington Branch, which is still around today, as well as the Whitestone Branch and the Central Branch, neither of which have any remaining track in Queens.

Residents in Whitestone, which is located north and slightly east and north of Flushing, began pushing for an extension of the line in 1913, before even the initial phase to 103rd St had even been built. Residents along the LIRR Central Branch wanted an elevated line along that right-of-way , which today is Kissena Corridor Park, stretching southeast of Flushing. The Public Service Commission, then in charge of such things, announced that it planned to extend the line beyond Corona (the neighborhood where Alburtis Ave, now 103rd St, the original terminal, was) through Flushing and further east, to Bayside. This extension would parallel the LIRR Port Washington Branch, as well as including a branch to College Point, which is located north and slightly west of Flushing. All of these plans were being proposed in 1913.

The LIRR, a private company, didn’t want the subway to be competing with its business in Eastern Queens, but offered to lease the Port Washington and Whitestone Branches to the City for rapid transit use for a period of ten years with an option for an extension of another ten years. Most communities in eastern Queens supported this plan, with the sole exception being Flushing, which continued to favor a subway being built under what would become Roosevelt Avenue, in the heart of Flushing. Had the lease plan been adopted, a connection between the IRT Flushing Line and the LIRR would have been constructed west of Flushing, likely around where the Willets Point Station is today, and bypassing the core of Flushing to the south.

However, as all of this was happening at the same time as the construction of the initial phase of the IRT Flushing Line, the Public Service Commission was not entirely focused on potential future extensions. The City and the LIRR were negotiating terms of the lease, but negotiations stalled in 1916, and impatience grew in the communities east of Flushing. The stall was largely due to the IRT and BRT, the two private transit operators that operated service on the Flushing Line. Neither company wanted to use the LIRR tracks, even though the BRT already sent some of its El trains in Brooklyn to the Rockaways over LIRR tracks during the summer months. Residents in eastern Queens were willing to pay a double fare of 10 cents at stations on the LIRR tracks in order to incentivize the IRT and BRT to the table. In October of 1917, a lease agreement was completed and the two private operators consented to running their trains over LIRR tracks.

However, there were significant challenges. The LIRR still wanted to run its own passenger and freight trains over the Whitestone and Port Washington Branches, which would need to be scheduled around the rapid transit services. Also, the Whitestone Branch had a significant number of grade crossings with local streets, and was only single-tracked. Both of these problems needed to be solved before rapid transit service was inaugurated, and both required significant capital investment to be fixed. Despite the lease plan being generally popular with eastern Queens residents and elected officials, the IRT issued a statement retracting its willingness to operate over LIRR tracks in November of 1917, just one month after the lease agreement was reached. The IRT did not provide any real reason as to why they withdrew. With that, the lease plan was dead, and focus once again returned to the subway under Roosevelt Ave, which was completed in 1928.

Also in 1928, the LIRR offered to give the Whitestone Branch to the City, in the same manner that the City would take over part of the New York, Westchester, and Boston Railroad in the Bronx for subway service. However, the City declined the LIRR’s offer, once again being put off by the high cost of double tracking and grade crossing elimination. However, a line beyond Flushing to College Point was being planned, that didn’t use the LIRR Whitestone Branch, and instead would travel along what is now 149th Street and 11th Avenue. Passenger service on the Whitestone Branch was ended by the LIRR in 1932, and the planned subway to College Point along 149th Street wasn’t completed. The City pivoted, and planned to take over the Port Washington Branch for rapid transit service in the wake of this failure, but that proposal never got off the ground as the LIRR was less willing to negotiate than they had been previously.

And then comes the dark age of American transit. The double whammy of the Great Depression and World War II kept material, manpower, and money out of the hands of municipal governments’ and transit companies’ coffers for all of one and half decades. Basic maintenance and upgrades weren’t even possible, let alone extensions to the existing network. The postwar economic boom in the US mostly left transit behind, as the G.I. Bill in 1944 provided loans for servicemen to buy suburban homes. The manufacturing plants, which had built the tanks and trucks of war, were retooled to produce the cars of the American Dream. Subsequently, this generation with newfound wealth abandoned cities for the Whites Only suburbia, decimating the revenue generating abilities of municipal governments and private urban transit companies.

In 1942, the 2nd Ave El was abandoned, and Flushing riders lost direct service to lower Manhattan for the first time since the line opened. In 1949, the connection between the Flushing Line and the Astoria Line at Queensboro Plaza was severed. The lack of funds for transit since 1929 (a problem which still exists today, nearly a century on) has meant that the extensions past Flushing into eastern Queens, planned since the beginning of the line, have never been built. Flushing is stuck with a station that is too narrow, because property owners along Roosevelt Avenue protested the damage to their buildings that widening the street would cause. It also suffers from an inefficient terminal station, because it was never planned to be the final terminal.

Despite no subway extension ever coming, eastern Queens grew rapidly anyway, and today Flushing-Main St station is the busiest subway-bus interchange station on the continent. It is the 10th busiest station in the city, the second busiest station in Queens (74th St-Broadway/Jackson Heights-Roosevelt Ave is busier), and the second busiest station outside of Manhattan. (Again, 74th St-Broadway/Jackson Heights-Roosevelt Ave beats it). Flushing-Main St beats Atlantic Ave-Barclays Center for ridership. Before the extension to Hudson Yards, the (7) train served the two busiest terminal stations in the city, aside from the 42nd St Shuttle.

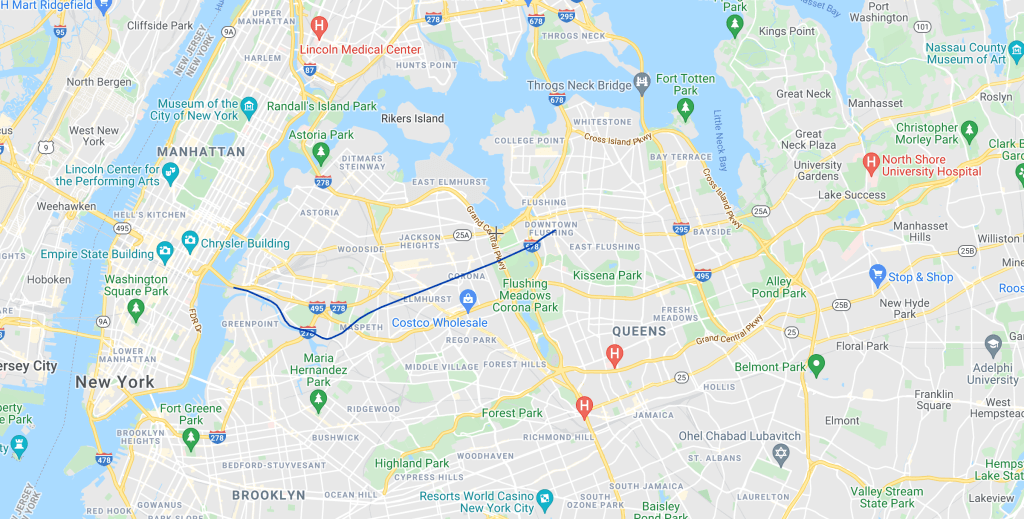

The IRT Flushing Line largely parallels the LIRR Port Washington Branch between 61st St-Woodside and Flushing-Main St. The LIRR Port Washington Branch is the only railroad line remaining to Flushing, but the history of railroad lines to Flushing is more complex and interesting than you might expect. If you thought the story of the Flushing Subway was intense, you ain’t seen nothing yet.

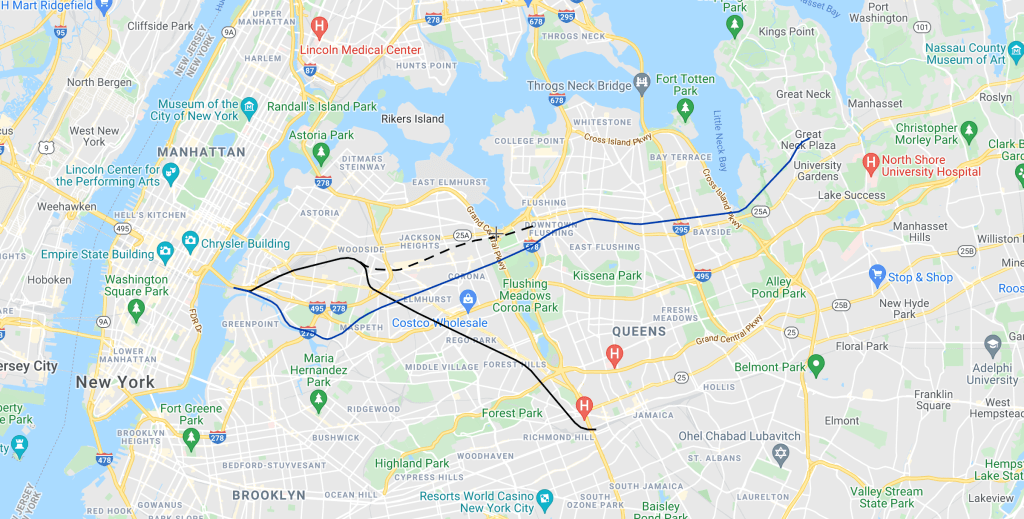

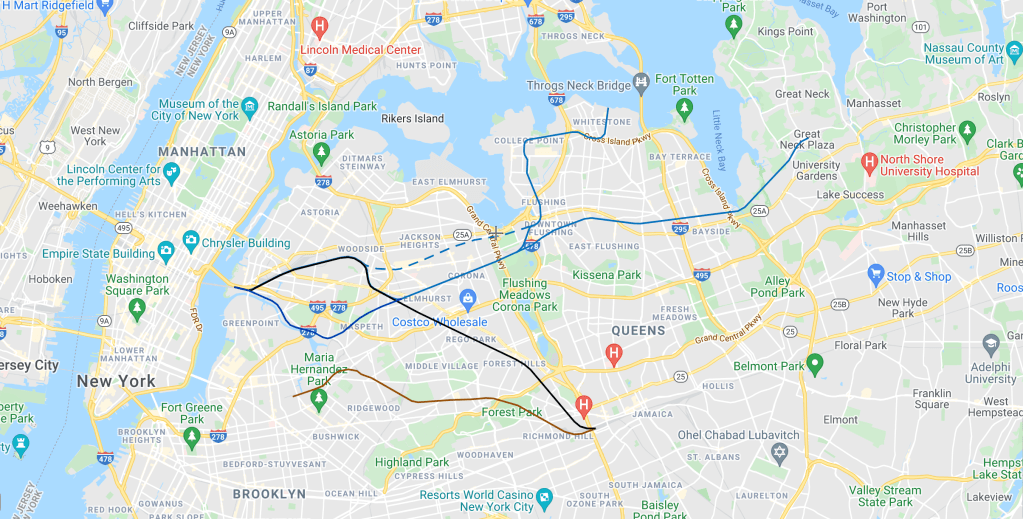

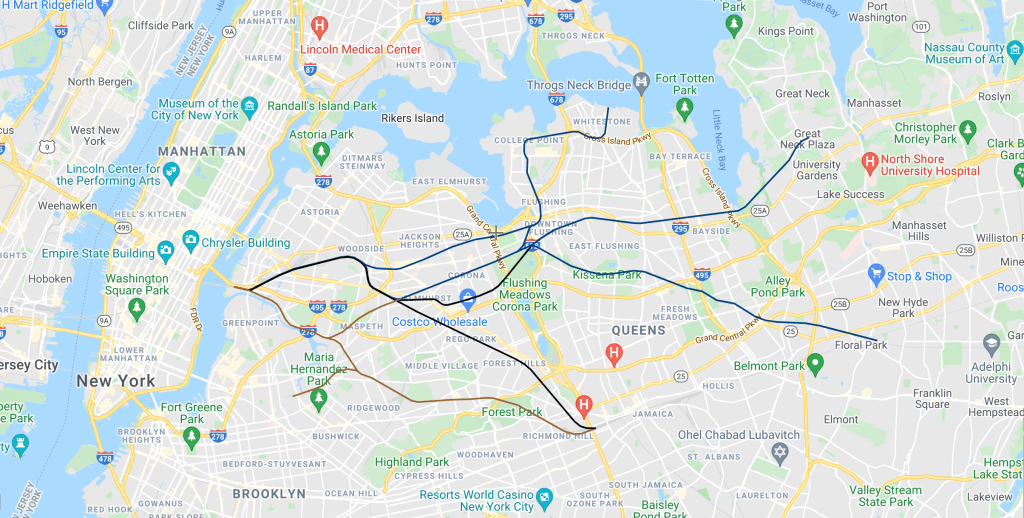

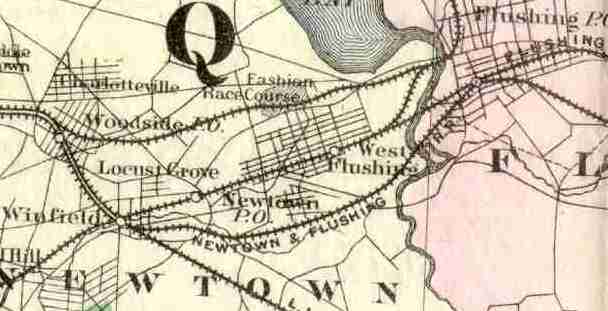

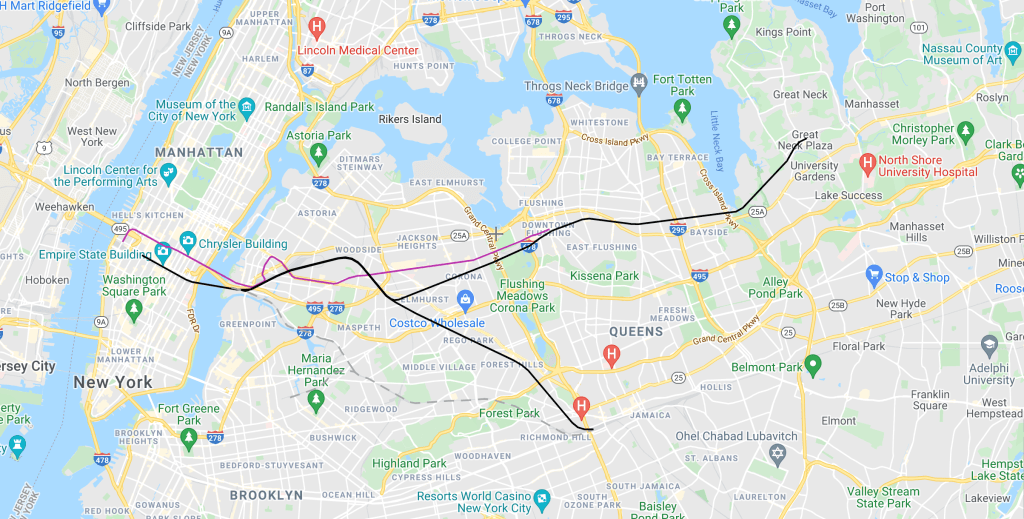

Fair warning, I research historical railroads in my spare time for fun, and this is even a little dense for me. I will do my best to explain it concisely. I have created maps to illustrate the development of the relevant railroads. The colors of each line refer to the controlling company, regardless of whether or not there were two separate legal entities. Dotted lines refer to railroads that are in place but not open to passengers. Keep in mind that many other railroads were being built at this time. These maps only show the relevant lines. For a more complete history of all railroads on Long Island, see LIRR History and Trains Are Fun.

1854

The Flushing Railroad is built between Hunter’s Point (todays Long Island City station) and Flushing. This was the second railroad on Long Island after the Long Island Railroad (which is the oldest railroad in the US still operating under its original charter). The line of the Flushing Railroad ran along Newtown Creek, before turning northeast at the intersection of 50th Road, 48th Street, and 49th Street (Queens street names are confusing) in the neighborhood of Maspeth. The line ran northeast in basically a straight line to Flushing, through the Mount Zion Cemetery (although the cemetery wasn’t built until 1893), along Garfield Avenue, and then along the route of the current Port Washington Branch all the way to Flushing.

1859

The Flushing Railroad is reorganized and renamed the New York & Flushing Railroad (NY&F), and establishes a subsidiary, the North Shore Railroad, with the intention of extending the line east from Flushing to Great Neck and on to Oyster Bay, another well established town on Long Island. Railroad history is littered with examples of an existing railroad chartering a new railroad in order to provide service to a new area. While there was technically a legal distinction between the New York & Flushing and the North Shore, the North Shore Railroad was, for all intents and purposes, just the New York & Flushing.

1864

The NY&F was known for poor service quality, and the dissatisfied residents of Flushing asked the LIRR to open a branch to Flushing in order to compete with the NY&F. And we all know that when residents of Flushing want something, be it religious freedom, a subway tunnel, or a railroad, they get it. The LIRR incorporates the Flushing & Woodside Railroad, and begins constructing a line from off of the LIRR mainline at Woodside towards Flushing.

1866

The NY&F reaches Great Neck, however the LIRR beats the NY&F to Oyster Bay, thwarting the long term plans of the NY&F (not shown on map). The LIRR opens its mainline between Jamaica and Long Island City.

1867

After the completion of the NY&F extension to Great Neck, the company encountered serious financial trouble, and sold the line to the LIRR. As this happened before the completion of the Flushing & Woodside branch that the LIRR was building, the LIRR decided to abandon the Flushing & Woodside, and instead simply take over service of the New York & Flushing. The point where the New York & Flushing crosses the LIRR mainline is called Winfield Junction. Both the NY&F and LIRR have a terminal in Long Island City, and now that the LIRR controls the NY&F, passenger service on the NY&F is routed over the LIRR mainline to Long Island City, rather than the NY&F route via Maspeth. From this point on, I am not always clear on the status of the New York & Flushing line south of Winfield Junction. Was it used for some passenger trains? Was it only used by freight? Was it used at all? I’m not entirely sure.

1868

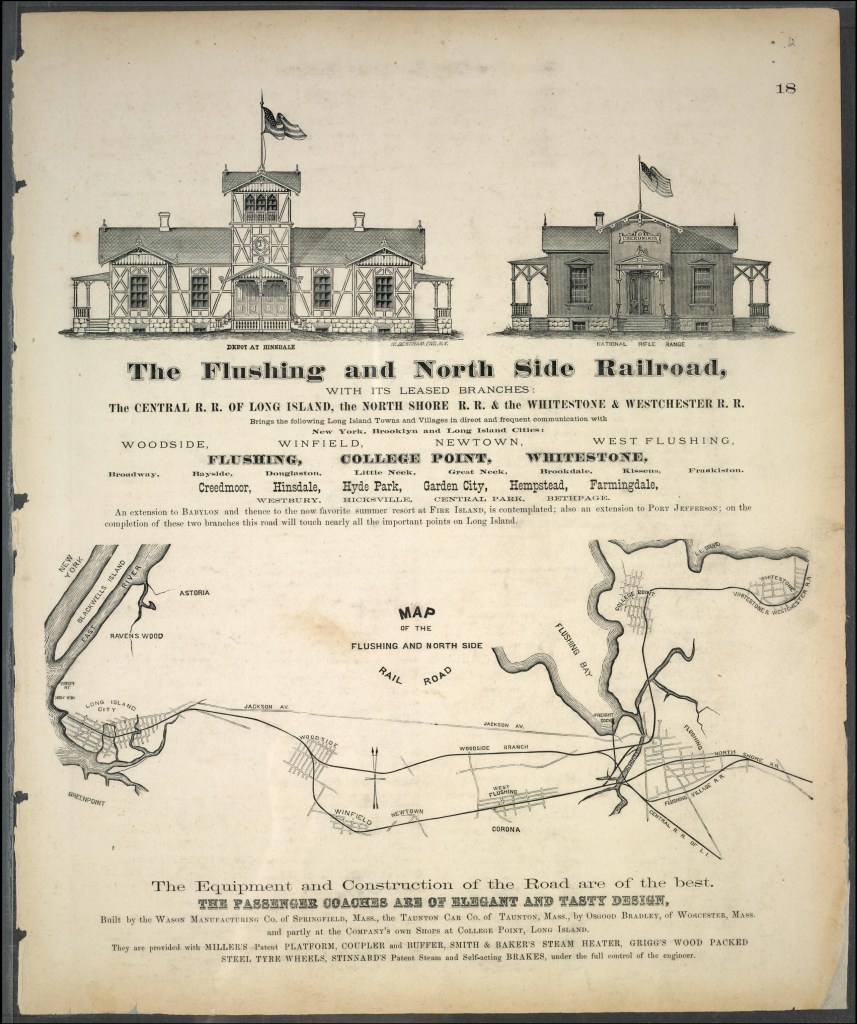

For some reason, Flushing residents were upset with this development, despite it seemingly being what they wanted in the first place: LIRR service instead of NY&F. However, they weren’t happy, and had Conrad Poppenhousen, a wealthy resident of the area, incorporate the Flushing & North Side Railroad (F&NS). The F&NS took over construction of the abandoned Flushing & Woodside line that had started construction under the LIRR, but had been abandoned before completion, and completed it.

The LIRR, which had basically just begun running services to Flushing over the old NY&F line, expected a monopoly on Flushing traffic. However, the NY&F track was in poor shape and required rehabilitation, and the potential competition from the F&NS line, made the cost of operating the NY&F too expensive for the LIRR. The LIRR, wanting to be rid of the line to Flushing sold the portion of the NY&F line north of Winfield Junction to the F&NS. The F&NS quickly built a connection between Woodside, where its Flushing & Woodside Line branched off of the LIRR mainline, to Winfield Junction. The NY&F continued to own the line south of Winfield Junction, between there and Hunters Point. The F&NS now owned two parallel lines to Flushing. The Flushing & Woodside was not yet open, and construction of it was deprioritized now that the F&NS had an operational route to Flushing and Great Neck.

1869

The F&NS opens a branch to Whitestone through a subsidiary (I told you this was common practice) the Whitestone & Westchester Railroad. As you might be able to tell from the name, the plan was to cross the East River/Long Island Sound and reach Westchester, although this never happened. This line becomes the LIRR Whitestone Branch, which Whitestone and College Point residents wanted converted to rapid transit as an eastern extension of the IRT Flushing Line. Remember that? This whole post is supposed to be about the subway, and yet here we are in 1869 (nice) looking at railroad lines in Queens County.

1872

The NY&F line along Newtown Creek is sold to another railroad, the South Side Railroad, which uses the former NY&F to reach the East River. This creates what is now known as the LIRR Lower Montauk Branch.

Conrad Poppenhousen, who owned the F&NS, had also gained control of another railroad on Long Island, the Central Railroad of Long Island. This line is now almost all but abandoned, but if you recall the planned extension of the IRT Flushing Line along the LIRR Central Branch, the Central Railroad is what would become the Central Branch. The Central Railroad was built in 1872, branching off of the F&NS just west of Flushing, and continuing southeast towards Babylon. A portion of this line is still in service connecting Farmingdale and Babylon.

1874

In 1873, the LIRR, in the immortal words of Katy Perry, changed its mind “like a girl changes clothes” and decided that it did want to compete for service to Flushing after all. It opened the Newtown & Flushing Railroad (once again one of those technically-separate-functionally-the-same railroad companies) and built a line to Flushing parallel to the former NY&F and Flushing & Woodside, which opened in 1874. This was south of the former NY&F line, but split off from the mainline at Winfield Junction. The Newtown & Flushing was nicknamed the White Line because of the bright white colors of its cars.

Conrad Poppenhousen merges his two railroads into a new one, the Flushing, North Shore, & Central Railroad (FNS&C).

The Flushing & Woodside is perhaps the most confusing aspect of this whole saga. It started construction under the LIRR in 1864, although it was abandoned before completion. The Flushing & North Side took it over, but soon gained access to the already operational New York & Flushing, and did not complete the Flushing & Woodside until, apparently, a decade after construction first started. My sources all seem to agree that the Flushing & Woodside, now called the Woodside Branch of the Flushing, North Shore, & Central Railroad, only opened for service in 1874.

1876

The Poppenhousen family had taken control of the LIRR. While the LIRR and FNS&C were technically separate, they competed with each other, and ultimately hurt the people with an interest in both. Therefore, in 1876, the LIRR closed the Newtown & Flushing line, in favor of the former NY&F and Flushing & Woodside lines. Eventually the FNS&C was merged into the LIRR formally.

1877

All service stops on the Woodside & Flushing Line. The LIRR now focused all passenger service on the former NY&F line, basically creating the modern Port Washington Branch. Between 1874 and 1876 there would have been three (THREE!) operational railroad lines between Long Island City and Flushing. By 1877, there was just one. And, despite all the maneuverings of the various players in this tale, the railroad we ended up with was basically the route of the original Flushing Railroad, which the villages of Flushing hated so much.

As we learned above, the Whitestone Branch held on until 1932, although the Central Branch was abandoned much earlier, in 1879.

The moral of the story is that Flushing has always been tough to serve with transit. I’m sure the people riding the IRT Flushing Line at rush hour these days sure wish they still had those two other railroad lines as options as well.

The IRT Flushing Line is one of the most fascinating lines in the city. Serving two of the most important stations in city, Times Sq and Grand Central, running through the oldest underwater passenger tunnel in New York, giving some fantastic views from the elevated structure, and reaching the busiest terminal station outside of Manhattan. In no small way, the IRT Flushing Line built much of modern Queens.

The calling of the New York Times fake news is uncalled for. You could have stayed it was a error in it’s reporting at a time. No need to give revisionists fuel.

LikeLike

The NYT is fake news. You are entitled to your opinion

LikeLike

So glad you’re back! Even though I’m not that big of a rail fan, I love your articles because they’re informative and detailed yet engaging. I just can’t click off! Thanks for the great read.

On Tue, Feb 15, 2022 at 12:10 PM Secrets of the Subway wrote:

> shirknado posted: ” Subway Map with IRT Flushing Line highlighted. Image > created by Leo Shirky, via the MTA Manhattan 34th St-Hudson Yards (7) 34th > St-Hudson Yards was initially planned as part of the city’s bid for the > 2012 Olympics, and the often-proposed but nev” >

LikeLike

Vernon-Jackson still has the original columns from the street car days (roughly in the middle section of the current platforms).

LikeLike

Was the Flushing and Woodside RR on an embankment or street level?

LikeLike

Given that it was built through mostly rural areas, and clearly not prioritized by the companies building it, I would guess that it was pretty much completely at grade with little to no elevation. However let me be clear that I don’t no for sure and haven’t been able to find evidence one way or the other.

LikeLike

Very good history of subway because I rode the 7 to main street from port authority to flushing

LikeLike

The closest remnant of the Flushing and Woodside RR I could find is on this website: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=https://maps.nyc.gov/then%26now&ved=2ahUKEwiK0LDtu5f2AhVUkYkEHWBFCGQQFnoECA0QAQ&usg=AOvVaw35PGjb0JYP8rvsoUNXE6DR

If you click on 1924, you’ll see the long gone Whitestone branch crossing over Flushing creek. To the left of it, there’s an open space where the Flushing and Woodside RR would have branched off. In addition, this open space aligns with another dirt road to the west and dead ends.

LikeLike

Yes, I love that map! I maybe should add an example from it to the post to illustrate what the railroads looked like in and around Flushing at that time.

LikeLike

Lastly, the Newtown and Flushing RR has no remnants so good luck with that 😂.

LikeLike